The Narrative of the Sovereign, Self-Governing People Is Harnessed by Elites to Legitimate Fundamentally Oligarchic States

The narrative and discourse of democratic rule and popular sovereignty, however alluring, are frequently employed for distinctly anti-democratic ends. Indeed, all too often the sovereignty of “the people” is invoked by elite actors to legitimate systems of government that are highly centralised and hierarchical, and easily leveraged to their own economic and political interests. The very same narrative that puts “the people” on a pedestal as the ultimate source of political power is also employed by political and economic elites to validate governmental structures that are fundamentally oligarchical or elitist, rather than democratic, in their structure and operation.

The Narrative of the Sovereign, Self-Governing People

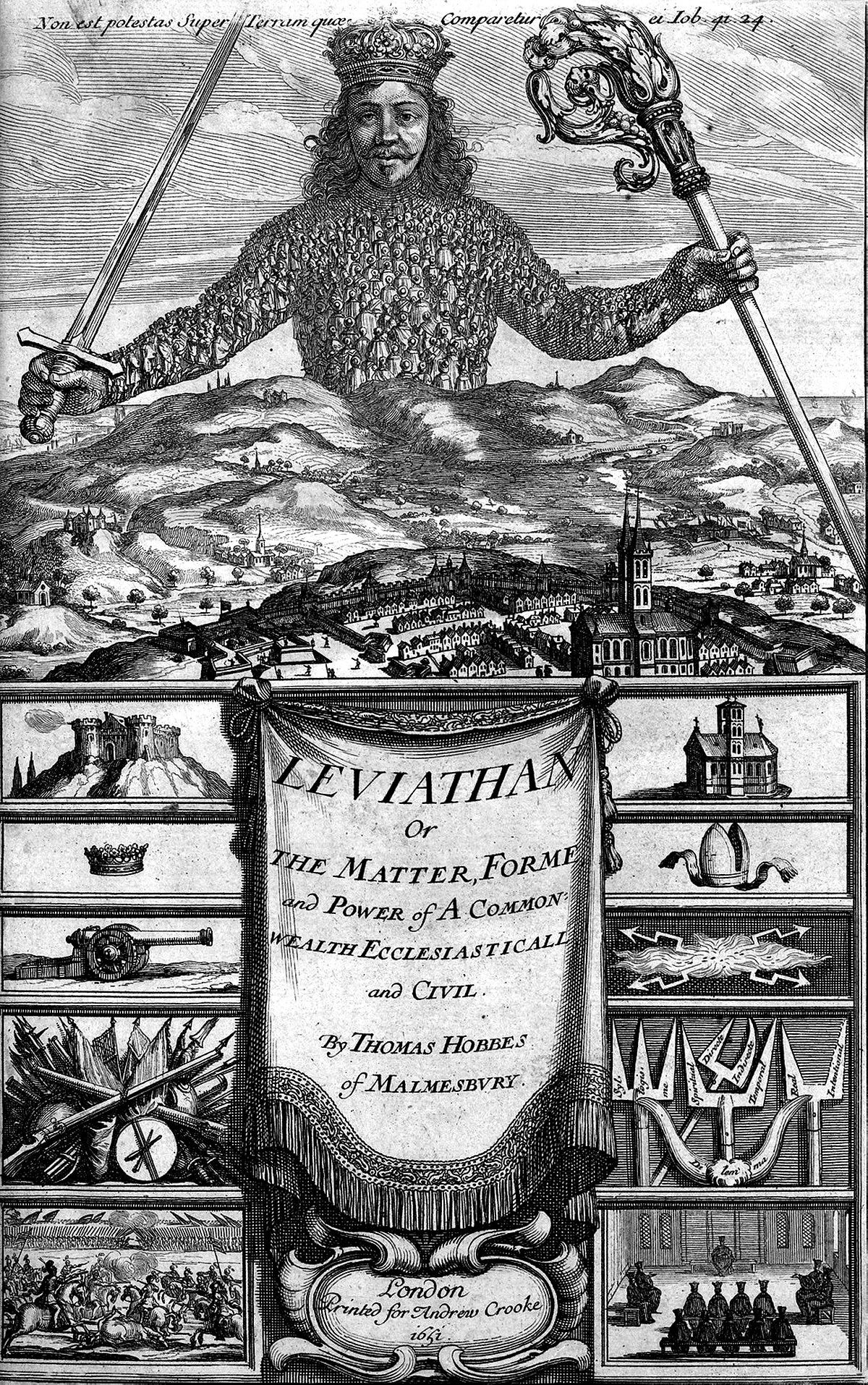

Western governments, most explicitly since the American and French revolutions, have generally rested their authority and prerogatives on the notion that they are somehow authorized in their public functions by the will of “the people” (typically “the people” of a national territory) who fall under their sway. The narrative of the sovereign, self-governing people repudiates the claim advanced by absolutist monarchs to exercise sovereign authority in the name of God almighty,1 and instead stipulates that “the people,” as the natural source of all legitimate political power, authorizes a body of representative rulers to rule in their name over a defined territory.

On this democratized account of sovereign authority, only certain social organs are entitled to wield public power, namely the judicial, executive, and legislative branches of the State, and their right to do so depends on some form of endorsement, whether tacit or express, prospective (say, a constitutional convention, a referendum, or election), or retrospective (say, re-election), by “the people” at large.

The Inevitability of Unequal Power

So far, so good. But if we scratch beneath the surface of the narrative of rule “of the people, by the people, and for the people,” we quickly discover that the true nature of modern government almost never lives up to the liberationist promise of popular sovereignty. This is partly because of the inevitability of unequal power in a large society; and partly because of the fact that most national States claiming the mantle of democracy are, in fact, highly centralised, and thus forego potential opportunities to mitigate power inequalities by giving power back to local communities.

Significant power inequalities are inevitable in large societies because in any group larger than a few hundred individuals, and certainly in any group larger than a few thousand, purely democratic rule – rule in which each person has an equal say – becomes impractical. Not everyone can be heard equally at the same time, or even over the course of the same deliberative process, because if they are, the process will take too long and quickly become dysfunctional. Similarly, not everyone can exercise the same measure of executive power, otherwise government is divided among thousands or tens of thousands of hands and no coherent governmental policy or decisions can be enacted.

In short, some element of hierarchy – the rule of a few over the many – becomes inevitable in anything larger than a very small and compact community. This does not mean that all hierarchies and power inequalities are justified, but it does mean that significant inequalities are hard-wired into any large society, whether we like it or not. The question is not how to abolish inequalities between rulers and ruled, but how to mitigate them or bring them within acceptable limits.

The Construct of “The Sovereign People”

The inevitability of inequality between ruling officials and citizens subject to their rule is clearly a problem for any society that claims to be democratic or that claims to embody the rule of the people. This problem has been addressed rhetorically in ancient and modern times alike, by telling a story in which the “people” is represented as a corporate actor that somehow holds political rulers answerable for their actions. The undeniable fact that some citizens exercise rule over others is effectively softened, by giving the “people” at large a corporate personality, and portraying the “people” in this collective capacity, as the true masters of political power.

This mythical construct of “the people” as a collective actor occupying the driving seat of political power may be lent some credibility by creating institutional mechanisms through which ordinary citizens can gain leverage over the political system, at least periodically.2 For example, in ancient Athens, ordinary citizens, taking their places within a popular assembly, could debate legislation and public policy, as well as ostracize or condemn to death political or military leaders deemed to have betrayed the public trust placed in them.3 In modern constitutional democracies, citizens periodically elect a small body of rulers to govern their society in what we hope are “free and fair” elections.