What follows is an abbreviated version of a presentation I gave on this topic to an Open Society sesssion organised by PANDA (Pandemics Data & Analytics). You can find the full video presentation on Rumble.

To support my work in defence of a free and open society, please consider sharing this post on social media or upgrading to a paid subscription.

Western strategies for mitigating the harms of the Covid-19 pandemic, like China’s, relied heavily on centralized, top-down governance. Expert knowledge and opinion played an indispensable role in providing scientific legitimation to that vertical, centralized response.

The problem is, as many people have already pointed out, pandemic interventions legitimated by expert opinion inflicted wide-ranging collateral harms (including untreated illness, poverty, depression, and the suspension of basic liberties) that are difficult to justify, especially when we consider the results of much more moderate approaches to disease management, such as those of Sweden and Florida, which were not worse than the results of a broad sweep of regions with intense and prolonged lockdowns.

If a class of experts with privileged access to policymakers goes badly wrong in its judgments, this may inflict significant harms on those affected by the policies and behaviour they recommend. However, as I explain below, the harms inflicted by official experts could have been hugely mitigated if expert advice had been given a more modest and humble role in the political process, and if expert committees had incorporated a much wider range of expert opinion. We should draw lessons from this analysis for the way expert opinion is availed of in future crises, be they global warming, terrorism, energy crises, or economic crashes.

What is “Expert Opinion”?

Let’s begin by unpacking an ambiguity in the expression, “expert opinion.” It might be understood as the opinion of someone who is truly knowledgeable or wise. However, for practical purposes, what mattered during the pandemic was that there was a class of persons considered knowledgeable and wise enough for their opinions about viral infections and related issues to be given special weight. So what I mean by “expert opinion” is simply the knowledge claims and perspectives advanced by individuals who belong to what is conventionally understood to be a class of experts.

The Official and Unofficial Role of Experts in the Pandemic Response

What role did experts actually end up playing in guiding the pandemic response? We should distinguish here between the role they officially played and the role they actually played. Officially, experts served on advisory committees, feeding governments with proposals and information, so that political leaders could use that advice and information to make independent decisions for the common good. Officially, there was a clear subordination of experts to rulers. Experts proffered advice; rulers took decisions. This is what happened, from a legal perspective.

In practice, things were often quite different. In many cases, experts were given a relatively wide berth to formulate their preferred policies and sell them to the public, while politicians basically rubber-stamped their decisions. The fact that expert voices could be heard on a regular basis at national press conferences, announcing or defending this or that new measure, made it clear that they were acting in what appeared, to all intents and purposes, as an executive rather than advisory capacity.

The fact that citizens often saw the face of medical experts at least as much as the face of politicians when pandemic measures were being announced shows that the border between advisor and decision-maker was blurred. We will return to this point later in our diagnosis of the failures and harms of expert advice during the pandemic.

How Expert Advice Failed Us During the Pandemic

Like it or not, both policymakers and ordinary citizens require the guidance of experts to make informed and rational decisions during a crisis. An expert can offer some rough estimation of the infection fatality rate of a disease, as well as who is most at risk from a virus. He may also be in a position to offer an informed opinion about how a virus is transmitted, or how the chain of transmission can be broken or attenuated. All of this input is invaluable both to the policymaker and to the ordinary citizen.

However, official experts committed colossal errors during the pandemic, for which ordinary citizens ultimately paid a high price. Here are some salient examples:

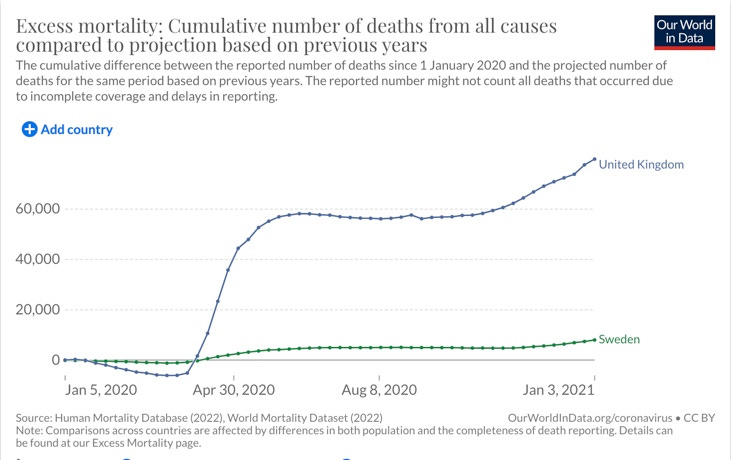

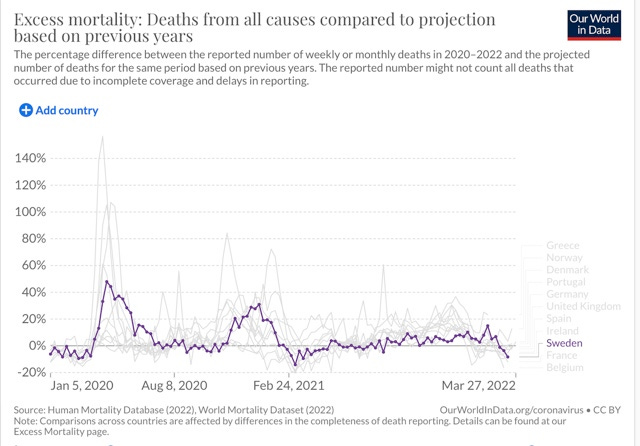

(i) Experts vastly overestimated the nature and extent of the pandemic threat. Neil Ferguson, for example, estimated that with strong social distancing policies for over 70s and isolation of cases, there would still likely be 250,000 deaths by the time the epidemic declined in the summer months of 2020. If we look at mortality levels in Sweden, which instituted this moderate policy and did not impose aggressive NPIs, we see estimated excess deaths from all causes for the whole of 2020 reaching just under 8,000 (based on charts produced by Our World in Data), which should have been around 50,000 if it had the population of the United Kingdom. That is just 16% of Neil Ferguson’s estimate of probable Covid deaths under a moderate social distancing regime, showing that Ferguson vastly overestimated the lethality of the virus.1

(ii) Experts vastly overestimated the efficacy of NPIs (non-pharmaceutical interventions) like lockdowns, border controls, and community masking at cutting down infections and disease, in spite of the fact that they were untested and only weakly supported by scientific studies. Again, this is shown by the fact that the UK and many parts of Europe, with relatively aggressive lockdowns, did not outperform Sweden in reducing excess mortality, with a very non-intrusive social distancing regime and no requirement to wear masks in public (aside from a recommendation to wear them on public transport).

(iii) Experts misapplied the precautionary principle by only considering risks on the side of Covid-19, not on other dimensions of public health and well-being.2 Experts gave little or no consideration to the far-reaching collateral harms of lockdowns and other emergency measures, including for children’s education, for mental health, for cancer patients, and for businesses. They seemed to only be awake to one sort of harm and one sort of good. It was as though the only thing that existed in their world was Covid and mitigation of Covid risk.

(iv) Many trusted experts failed to anticipate the vast collateral harms of lockdowns, even though many of their colleagues were warning about these collateral harms from early on in the pandemic. A rounded view of societal lockdowns could not possibly miss the fact that a systematic paralysis of social and economic life would have far-reaching repercussions for education, mental and physical health, poverty and unemployment rates, and so forth. Yet high-level “experts” somehow missed all of this, and hardly even discussed it even as they gambled on the life-saving power of lockdowns and related restrictions.

(v) Experts relied on a crude form of utilitarian thinking that subordinates basic human rights, such as informed consent, to a utilitarian calculus concerning the most efficient way to get certain public health benefits. This is demonstrated by the fact that experts recommended measures like vaccine passports, that are inherently coercive and inconsistent with the principle of informed consent, in return for some anticipated reduction in infections (a reduction that ultimately proved to be marginal).

These failures of public health expert advice translated into ineffective and counterproductive policies, whose consequences will haunt us for years to come, such as an educational deficit, fatal delays in cancer screenings, the collapse of many jobs and businesses, the separation of many families, the expansion of online corporations at the expense of street retailers, the suspension of informed consent and individualised medicine, and the abridgement of civil liberties.

Why the Failures of Expert Opinion Proved so Catastrophic

There is no doubt that many of the judgment calls of government-appointed experts turned many citizens’ lives upside down, with no clear benefit either to public health or human well-being more generally. In part, this was the result of certain blindspots and errors committed by experts drawing conclusions from incomplete information and knowledge. But it was also due to the way expert advice was translated into the institutional structures of national governments, and the way the role of experts was conceived during the pandemic.

If the role of experts in governance had been conceived and institutionalised more modestly and prudently, I believe we could have avoided many of the catastrophic consequences of the pandemic interventions. So how was the role of experts conceived during the pandemic? Here are four problematic features of the institutional and public role of experts in pandemic decision-making:

(i) Confusion Between Advisory and Executive Roles

First, experts were given a sort of de facto executive, decision-making power, a power that was augmented in some cases by their celebrity status, with frequent press conferences announcing the latest “measures,” with messages congratulating or reprimanding the public, etc.

Formally, they never held executive power, but their voice became so overwhelming and pervasive that it was no longer clear that they were merely serving as independent scientific advisors to governments. The omnipresent role of Dr Anthony Fauci and the Center for Disease Control in formulating and leading public health policy in the United States is a clear case in point. This confusion between executive and advisory roles had deleterious consequences for the public interest:

First, the towering public role of experts like Dr Anthony Fauci made it more difficult for political representatives to engage in a truly open-minded conversation about the common good and act on more rounded assessments with the input of other experts besides the public health “gurus.”

Second, the confusion of roles made true accountability difficult, because politicians were officially in charge, yet seemed not to be calling the shots. So politicians could blame public health gurus for mistakes made, and public health gurus could blame politicians for the consequences of their own recommendations.

(ii) Insufficient Disciplinary Breadth of Expert Committees

Second, by constituting expert committees along very narrow disciplinary lines, almost exclusively medicine, epidemiology, and behavioural science, governments silenced the voices of other relevant disciplines, like economics, law, and political science, voices that would have been critically important for broadening the imagination and vision of medics, who were often tone deaf to the economic, political, and legal ramifications of their recommendations. In addition, there was a perception that expert committees had to be unified in their opinions. But a healthy does of dissenting opinion would have moderated some of the more radical elements on exerpt committees.1

(iii) Failure to Adequately Distinguish Technical from Rounded, Holistic Assessments

Third, governments failed to communicate the difference between specialized, technical judgments about the efficacy of this or that measure along this or that dimension of utility, and rounded prudential judgments about the common good. Expert judgments about infectious disease control were too often presented as definitive judgments about the common good, which would need to take on board a broader range of considerations, including economic sustainability, civil liberties, and rule of law.

(iv) Routine Reliance on Coercion and Police Power

Fourth, expert advice about individual behaviour was routinely and seemingly automatically reinforced by coercive and economic sanctions applied to dissenters. This was a radical departure from past uses of expert knowledge during pandemics, which had relied on voluntary compliance with public health advice. The routine reliance upon coercion made expert error far more dangerous than it would be under a voluntarist regime:

First, in a voluntarist regime, expert advice has to be sufficiently well evidenced and persuasive to the public to induce voluntary compliance. Advice that is either poorly supported from a scientific perspective, or radically at odds with the common sense of the community, would not be widely observed. This vital check on expert advice is removed in a coercive regime.

Second, in a voluntarist regime, general principles can be adapted to local circumstances with flexibility and discretion. For example, if there is a recommendation to avoid social contact, this can be balanced by considerations of compassion or mental health by local actors. In a coercive regime, public health directives may be imposed willy-nilly, leaving little room for creative and compassionate adaptation to local circumstances.

(v) Unacknowledged Conflicts of Interest

Scientists whose institutions or research activities heavily relied on private funding, including funding from the pharmaceutical industry, had a clear conflict of interest when pronouncing on topics that affected the finances of their donors. For example, experts working for the World Health Organisation, which received large amounts of private funding, including from individuals like Bill Gates who have very well defined opinions about vaccination, would be susceptible to bias in favour of corroborating the opinions of donors, rather than undermining those opinions.

Last but not least, experts were much more likely to receive large amounts of funding to run randomised trials testing patented drugs than un-patented, re-purposed drugs like Ivermectin, which were not going to make much money for anyone. The high level of dependence of scientific research on funding provided by large pharmaceutical companies with massive stakes in society-wide vaccination campaigns and in the sale of their pharmaceutical products generates a clear conflict of interest, yet this conflict of interest was barely discussed by mainstream journalists.

Some General Conclusions for the Responsible Use of Expert Opinion to Manage Future Public Crises

With our diagnosis of the catastrophic harms inflicted by bad expert advice during the pandemic, we are in a good position to propose constructive steps that can be taken to mitigate the risks associated with misguided expert advice.

Here are five steps suggested by my diagnosis:

1. Executive power must be more clearly separated from the authority of expert opinion. Give experts less public prominence. Politicians must be the ones directly taking the decisions and must be the ones answering to the public for those decisions.

2. Expert committees must incorporate a much wider range of voices, including dissenting perspectives, even if this makes recommendations harder to formulate. Expert committees cannot be monodisciplinary or bi-disciplinary, and it is advisable that they include individuals who can make a strong case for dissenting perspectives.

3. Both politicians and expert advisors must be very careful to distinguish between technical and highly specialized judgments about crisis management. For example, holistic judgments about societal risk and the demands of the common good are not the same as technical judgments about whether a particular measure is likely to bring down the “R number.” Politicians must also make this distinction clearer to the public.

4. Expert advice should not be routinely reinforced with coercive sanctions directed against law-abiding citizens, especially in connection with matters like public health. Coercion drastically reduces the capacity for adaptation of public advice to local circumstances. Experts should have a pedagogical rather than coercive relationship with the public. This can be achieved by changing the culture of crisis management. But efforts at cultural reform are not always successful without institutional reinforcement. So there must be strict constitutional limits on the use of emergency powers, as there were in Sweden.

5. Conflicts of interest affecting expert opinion should be openly acknowledged and reported, not only in academic publications but also in journalistic coverage of scientific studies. These conflicts of interest could be generated by the dependence of experts on private funding, for example funding by the pharmaceutical industry. Organisations and individuals that undertake research relevant to public policy, or exercise important advisory roles, should be carefully vetted by governments and journalists to ensure their advice is not tainted by serious conflicts of interest.

Undoubtedly, there are many more steps that could be taken to prevent the sorts of catastrophic harms we saw during this pandemic as a result of unsound expert advice. But these five would certainly be a good start.

Thanks for reading! To support my work in defence of a free and open society, consider sharing this post on social media or upgrading to a paid subscription, which unlocks all blog posts.

Don’t forget, you can also find me on Youtube, Rumble, Telegram, and Spotify.

This post is an abbreviated version of a presentation I gave on this topic to PANDA (Pandemics Data & Analytics), which can be found here.

Here are some of the posts you will unlock with a paid subscription:

Monocentrism vs. Polycentrism: Two Competing Images of Civil Order

On the Nature of a Free and Open Society, and Why It's Worth Fighting For

How Might We Promote More Functional and Thriving Neighbourhoods?

Six False Beliefs About Science

Are Western Democracies on the Brink of a Regime Change?

Is Civil Society Strong Enough to Withstand the Menace of Democratic Despotism? - Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

The Narrative of the Sovereign, Self-Governing People Is Harnessed by Elites to Legitimate Fundamentally Oligarchic States

Mask Mandates Sum Up All That Is Wrong with the New Covid Regime

This becomes clear if you examine the makeup of the expert committees formulating public health recommendations during the pandemic. Consider, for example, the makeup of Ireland’s National Public Health Emergency Team (as reported by The Irish Times on April 30th, 2020). There is a conspicuous absence of just about anyone with expertise not narrowly focused on medicine and public health.

Dr Tony Holohan, chief medical officer at the Department of Health.

Prof Colm Bergin, infectious diseases consultant at St James’s Hospital and Professor of Medicine at Trinity College Dublin.

Paul Bolger, director of Department of Health resources division.

Dr Eibhlin Connolly, deputy chief medical officer at the Department of Health.

Tracey Conroy, assistant secretary in the acute hospitals division of the Department of Health.

Dr John Cuddihy, interim director of the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC).

Dr Cillian de Gascun, director of the National Virus Reference Laboratory in UCD.

Colm Desmond, assistant secretary for corporate legislation, mental health, drugs policy and food safety division in the Department of Health.

Don’t forget the capture of institutions by commercial interests. The “experts” were interest-conflicted, as were the institutions where they worked.

Thank you for the interesting and thought provoking article. I have a few comments:

1. There is no doubt that many assumed that people in positions of power (such as Fauci) were experts. IMHO, however, the main problem is that true experts were not listened to. Dr. McCullough was ignored about early treatments. Dr. Malone was dismissed. Dr. Cahill was silenced. Dr. Bridle was ousted. Dr. Gupta was discredited. Even Canadian crisis management expert, David Redman was given a deafening cold shoulder. In very fact, the experts in epidemiology, virology, immunology, medicine, and crisis management were systematically ignored and silenced. They are outcasts to this day.

2. While it is true that chief medical officers became the face of the covid crisis, and that they announced the newest measures, this does not necessarily mean that they were actually the ones making the decisions. Watching my local CMO convinced me that he was being bullied and pressured to tow a specific line. For instance, at his daily press conferences, the MSM hounded him day after day about bringing in a mask mandate until he buckled and brought one in (against his own stared opinion about mask effectiveness).

3. I knew in Jan 2020 that the covid scare was a Chinese hoax: what was being said and done about this coronavirus defied all basic biology and medicine. I knew by March of 2020 that the IFR of covid was hardly worse than a mild flu, and that it primarily killed the old and infirm. By April I was writing letters advising governments that lockdowns would kill more people than covid. It did not take an expert to see any of this. Every real expert should have known the same.

4. The fact that the majority of governments around the world acted in lockstep offers to me pretty convincing proof that the problem is not about how governments related to their chief medical advisers or official "experts." Each country, state or province should have had their own independent and previously defined relationship. Most countries had a pandemic plan, only to drop it when covid hit. This tells me that the problem will not be resolved by more legislation or better definitions of roles.

5. To me, living in a technically advanced country, it is a public embarrassment what we did in response to covid. The big question is how were medical advisers and officers that should have known better, either so grievously mistaken or so entirely convinced to act against their own knowledge and education.